Infrastructure Week: Connectivity

Architects are famously known for resolving spaces according to geometric or aesthetic principals. To this end, we’ve honed our abilities with certain design tools, computer software, and thought processes that lend themselves to this compartmentalized way of thinking about the built environment. However, when it comes to the urban environment, there is tremendous power in thinking about its structure and organization as a system of interconnected and interdependent networks. Network-thinking emphasizes the importance of the relationships between multiple sites and gives consideration to the fact that small shifts in balance or orientation of a single component can have enormous effects throughout the rest of the system. This way of thinking reveals the importance of the connections themselves – the infrastructure – between the various components.

Connectivity is a central concept for our recent winning entry for the Master Plan Design Competition for LaGuardia Airport. Our entry, titled Port LaGuardia reconceives the airport as a fully integrated transportation center that acts as a flow-through portal, rather than the terminus of a journey. Through a number of strategic moves, we proposed a seamless, multi-modal connection to the LaGuardia airport, employing existing and new modes of transportation – with a focus on the traveler’s experience. Approaching the challenge through the lens of connectivity, PORT LAGUARDIA channels the flow of people, goods, and services through the most congested airspace in the nation to a regional multi-modal ground transportation network. The airport terminal becomes a component of a complex multi-modal network that includes a new multilevel circulation spine. The result is an efficient, world-class system, and a welcoming gateway to the city and region.

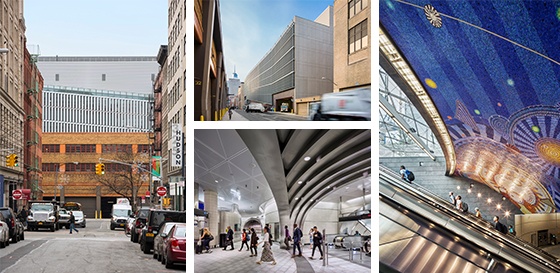

When we design infrastructure spaces and facilities, we think about them in terms of how they fit into the physical framework, as well as how they contribute to the experiential framework of the city. For example, our approach to designing transportation facilities, like the Hudson Yards – 34 Street Station, carefully considers both the required passenger and vehicular flow as well as the human interactions and the passengers’ experience. The station entrances are integrated into a new 3-block-long park and are graced with brilliant public art. Inside the station, the passenger is intuitively guided through the sequence of spaces and experiences to provide the connection from Street Level to the Platform 120 feet below. The brightly-lit column-free station platform and mezzanine, as well as the awe-inspiring 80-foot-high escalator and inclined elevator tunnels contribute to the quality of the passenger’s experience – as evidenced by the public’s overwhelming response upon the station opening! In terms of connectivity, the station’s impact reaches far beyond its entrances in the park – it has spurred the incredible redevelopment of the Far West Side of Manhattan. Similarly, in designing the Manhattan Districts 1/2/5 Garage and Salt Shed – a “Not In My Back Yard” building type – we thought about how to marry the facility with the neighborhood – the result is a sculptural landmark, much-loved by the community. The facility also has a complex program as a critical component of the city’s sanitation and snow removal network. We used the architecture to turn a NIMBY into a YIMBY!

As our cities continue to expand and grow, both in size and complexity, our approach to designing the buildings that make-up the urban framework – the infrastructure – will need to evolve. In many cases, these are structures and uses that communities think of as undesirable. The challenge to Architects and Urban Designers is to design – not just for the client’s and the public’s acceptance – but rather for the possibility of strengthening people’s connection to the building, to the city, to the Earth, and to each other.